MAPS AND EXPLORATION

Joe Cruz

A map is a dialogue between clarity and silence. The clarity is in tracing a path through a far away place, or revealing what was otherwise hidden in familiar neighborhoods. A map is an indispensable guide, a source of confidence, and a means for locating oneself in safety and motion. But the silence of maps—that which is unsaid and left out—is even more important. Marks on paper or on a screen remain far from the lived texture of the experience once you get there. The map leaves out what it is going to be like to watch storm clouds form in the distance, or the conversation with a farmer in her field, or the way that passing through the gridded roads of a town is a chance to stop a while and kick a ball with kids. The silence of maps is an invitation to vulnerability and humility.

Maps are symbolic but are also pictorial and aesthetic. The picture-like quality of a map makes it different from a story or a set of equations in that our transit through the information on a map isn’t linear. Maps invite motion and emotion as we enter into the depicted space. Your attention can fix on dense contour lines of a high ridge, and from there you might go searching for the most accessible path to a saddle. Or you might dwell on a green patch and wonder if that might make for a good place to camp. Looking at a map is in miniature the very exploration that consulting a map is preparation for, open-ended and dynamic and ebbing and flowing with excitement or confusion.

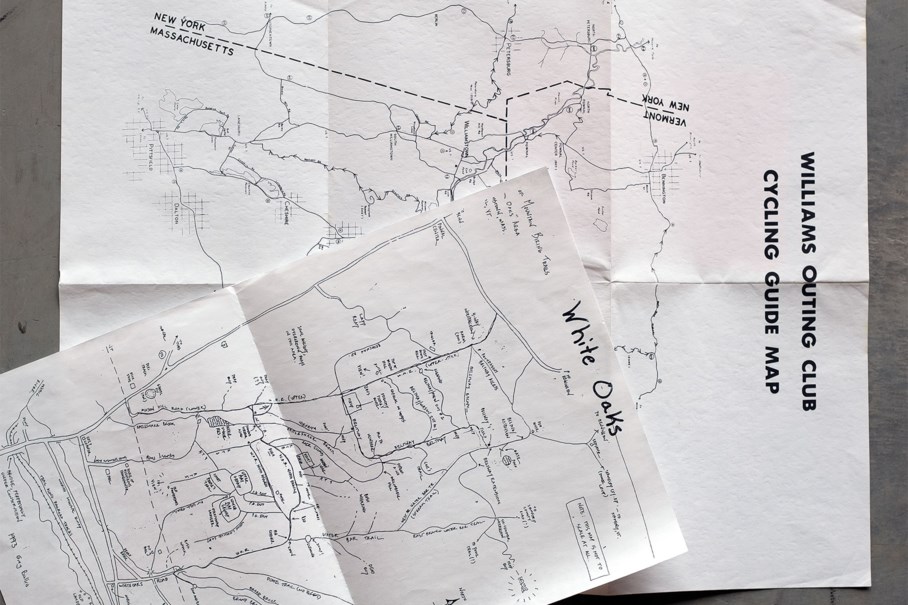

My own cycling adventures began with hand-drawn portrayals of local trails, not even remotely to scale. They were collisions of collective recollection of tenuous accuracy, with the goal of sharing and preserving. Longer trips meant stopping at gas stations to get an advertisement filled automobile map of the county, only to discard it once its border was reached. A tourist brochure or a diner placemat might capture broad but still helpful directional relationships between places. All of these paper maps have edges, in contrast to the infinite scroll of electronic resources. I appreciate the honest confession of finitude of those old maps.

Photo by Donalrey Nieva

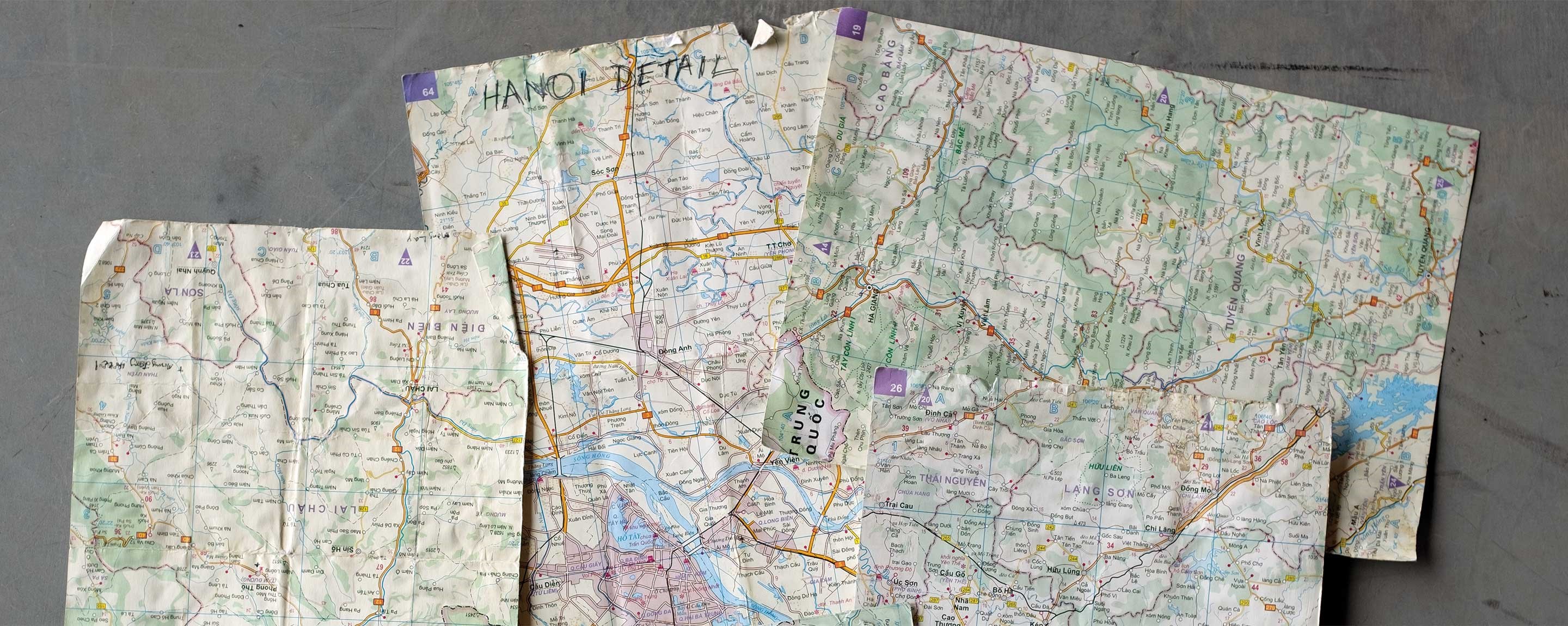

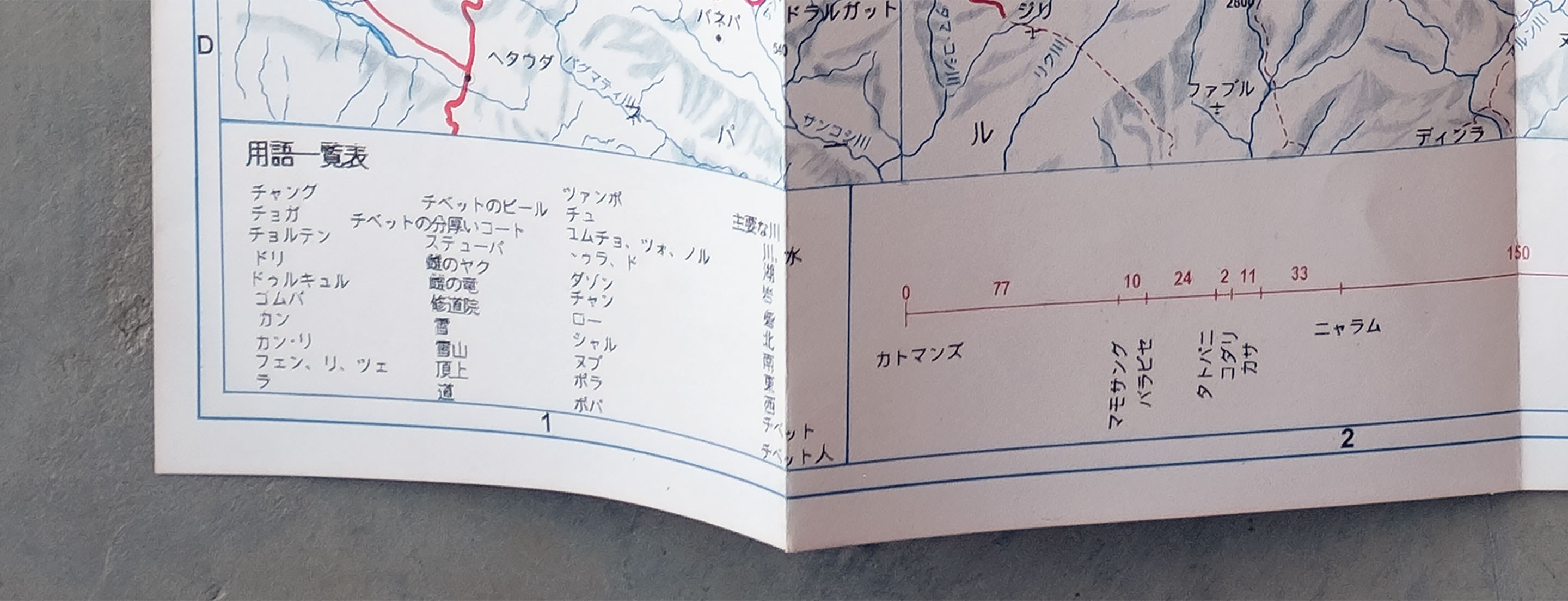

Back in the late 1980s, I phoned a bike shop in Moab—I got the number from calling the Utah area code directory assistance—and the person who answered helpfully indicated that they had a recently published map of Canyonlands National Park that they would send to me if I sent them a self-addressed stamped envelope along with a check. A couple of weeks later I had in my hands the talisman that would give me the security to set out around the White Rim Trail on my first bikepacking trip. Fifteen years on, while bikepacking in Pakistan, India, Nepal, and Tibet, one of the most precious items in my pack was a plastic bag with a sheaf of pages from used bookstore editions of Lonely Planet, photocopies of borrowed foldouts, and notebook entries consisting of little more than dots with place names connected by lines with a number indicating kilometers. Over lunch I would consult these as if they were a deck of future fortunes. Explorations still for me start with a map unrolled on a tabletop, eyes scanning from corner to symbol to contour, and with my imagination pretransporting myself in anticipation and wonder.

Maps tell us something important and real and speak the truths that went into their making, but those truths are specific and narrow, and that is where silence looms again. The silence risks colossal failure because it can actively quiet the history of the landscape. It can become a brazen ignorance, as if the map is a complete reckoning of a place. The silences are the inevitable result of abstraction away from detail, time, and change. That’s the dangerous side of exploration as an idea, as if we’re going where no one has ever been. Or, even if we know that that can’t literally be true, we can yet end up letting our own narrative fill up the space, which ends up making invisible the people who were already there. On a bicycle, one is almost always moving along a path placed there with intentions perhaps different from one’s own. When I created the route for an expedition style ride in Kyrgyzstan, I used the Soviet Union’s cartography of the region. These sheets were made to be kept secret and for purposes of state and control.

United States Geological Survey maps are a triumph of science and understanding, but they are also a legacy of displacement of cultures and instruments of possession and extraction. Who was displaced by colonization or industrialization? Who built the track or the road or path, who placed the stones just so? Maps have a history that they are sometimes reluctant to tell.

For some trips I had a binder clip affixed to a brake cable housing so that the pages could lay across the stem and bar, readable at a glance. Other years it was important that the handlebar bag have a transparent top patch, as touring bags in the ascendency of plastic all used to, even if condensation, glare, and yellowing from age were limiters. Often, it was a matter of committing to memory sequences of turns at road intersections, repeating the mantra off and on for a few miles so as not to have to take the precious map out of a pocket or perilously unfold it for fear of a tear. I still do it that way sometimes, the mnemonic repetition helps with the meditative aspect of a ride.

It often used to be more straightforward to search for a map upon arrival at a destination. On a memorable second day in Quito, I made my way to the map counter on a military base—my passport left at the front gate—to look at declassified Ecuador quadrangles for my trip southward. But maps aren’t, or need not be, an essentially commercial enterprise. A story at a bar that yields a map drawn on a napkin crystallizes whereabouts that originate in the joviality of the time spent together. In Peru I talked to two separate sources and had them draw maps of a tricky area so that I could compare the two. They were, of course, different stylistically, and they were remarkably different informationally. Nor could it be said that their intersection was somehow the truth. Instead, they each captured something different, some practical engagement with the environment, some salience that I could participate in and that could be synthesized into my own locationing.

It’s easy enough to describe navigation before electronic resources and GPSes were ubiquitous, but the description leaves out the concrete dimensions of gathering the material, making it durable for use for weeks on end, and the execution of the skills of map use. Memories are most robust when they are formed through multiple senses, and some of mine include the musty paper smell of my oldest maps when I pull open the file cabinet drawer. Some of my maps feel geometric and precise from careful creases, while others are malleable and blunt from constant handling. Maps crackle and scrape as they’re unfolded, they rustle like leaves of a tree of optimism as they are held down against gusts. For some precious maps, not in the sense of being valuable but rather crucial for the success of a trip, I would laminate them or print them out on waterproof material, giving them a silky texture that is wrong for paper things but right for field checks.

I’m not anti-technology. Sophisticated mapping resources have changed the way we can approach adventurous rides.

Shareability of mapping resources has increased the possibilities for being outside, and I admire that. In creating routes for myself or others, for local day rides or for months-long expeditions, I’m constantly flipping between map layers—OSM, Google, USGS topo—and comparing them to the satellite image. The practicality and sheer flexible power of digital mapping is revolutionary. It opens the world, makes it accessible, maybe in some senses more egalitarian.

What we’ve lost should also be acknowledged, though, and paper maps have a role in adventure planning beyond nostalgic memorabilia. It would be a shame to forget maps that are idiosyncratic and more frankly distortions. It would be a shame because salience honors local knowledge, much the way that our own recollections of explorations are an encoding of what we take to be meaningful and important. Some kinds of explorers have denied that maps have silences, and have instead tried to make it seem that their own journey is the first, last, and complete reckoning. I want no part of that. But we can explore our own reactions and meanings and creativities about a span and land. In the best cases those reactions can be on the way to understanding.

Photo by Logan Watts

I’m glad for the literal and figurative blank silences on maps because they inspire us to investigate more seriously what and who was left out and to be thereby ourselves changed. That’s exploration.

Joe Cruz is a lifelong bicycle adventurer and a professor of philosophy. He is the creator of numerous well-known bikepacking route maps, including the VTXL, the course for the early editions of the Silk Road Mountain Race, and tracks in Slovenia, Peru, Cuba, and many others. A proud Nuyorican, he splits his time between Southern Vermont and New York City.